Figure 1. Right non-healing transmetatarsal amputation with areas of necrosis and areas of non-healing.

Advanced Limb Salvage With Failed Infra-Popliteal Bypass Revascularization

Patient with “No Options” and Planned Major Amputation

Kumar Madassery, MD

Critical limb ischemia (CLI) is a devastating diagnosis due to the natural course of the disease, which typically coincides with several comorbidities that get exacerbated. The sad truth is that preventative management decades before the diagnosis could help to prevent the scores of associated deaths we witness yearly. However, what we are left with is the ongoing and challenging task of fighting vigorously to save limbs from major amputation, which, if it occurs, leaves the patient with an over 50% mortality rate within 4 years. Long ago, surgical revascularization was the only option, if any, to improve perfusion to a patient’s distal lower extremities, many times with restricted opportunities due to lack of autologous veins and lack of distal arterial targets. Over the years, increasingly innovative endovascular salvage approaches and techniques have been developed, which in many cases have prevented major amputation for patients at the “terminal arterial cancer” stages.

In this case, we describe a patient facing major amputation after prior surgical bypass and progressive transmetatarsal amputation (TMA) site wounds, with successful endovascular revascularization.

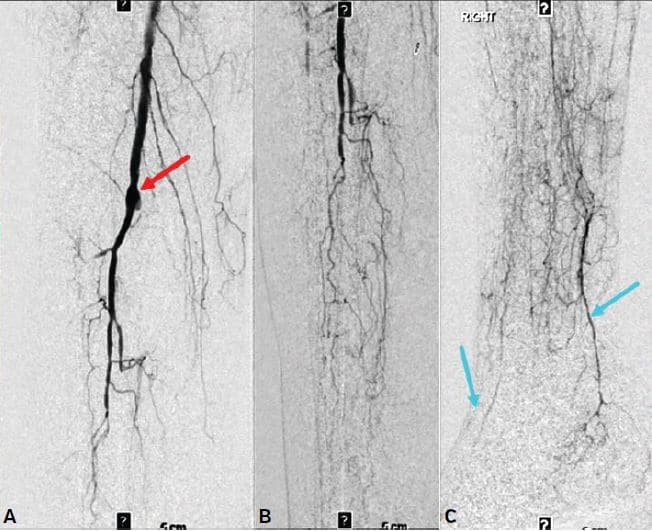

Figure 2. Infra-popliteal angiograms showing (A) proximal hood (red arrow) of the occluded right P3 to posterior tibial artery bypass with occluded anterior tibial, peroneal, and posterior tibial arteries; (B) extensive diminutive collateral network in the mid to distal leg; (C) subtle and diminutive reconstituted short segments of the distal posterior tibial and dorsalis pedis arteries (blue arrows) with no significant outflow in the mid and forefoot.

The sad truth is that preventative management decades before the diagnosis could help to prevent the scores of associated deaths we witness yearly.

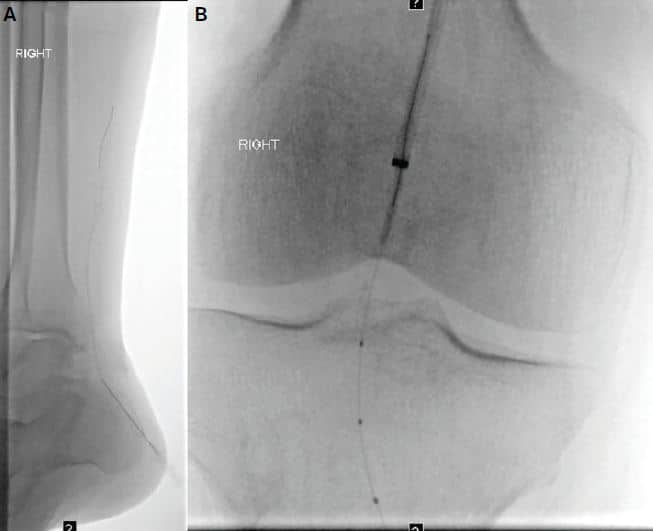

Figure 3. (A) Retrograde tibial access with micropuncture into the small posterior tibial artery. After successful traversal into the popliteal artery, (B) successful flossing of retrograde wire through the antegrade base angled catheter.

Case History

A 67-year-old male with a past medical history of insulin-dependent diabetes, coronary artery disease with prior coronary artery bypass surgery, and peripheral vascular disease with prior right-sided popliteal to distal tibial bypass due to “acute severe lower extremity compromise” approximately 10–15 years prior to presenting to our center. The patient had developed dry gangrenous wounds of the great toe and second digit in the past. These wounds had been managed with wound care, medical management, and surgical debridement, eventually necessitating toe amputations and then TMA.

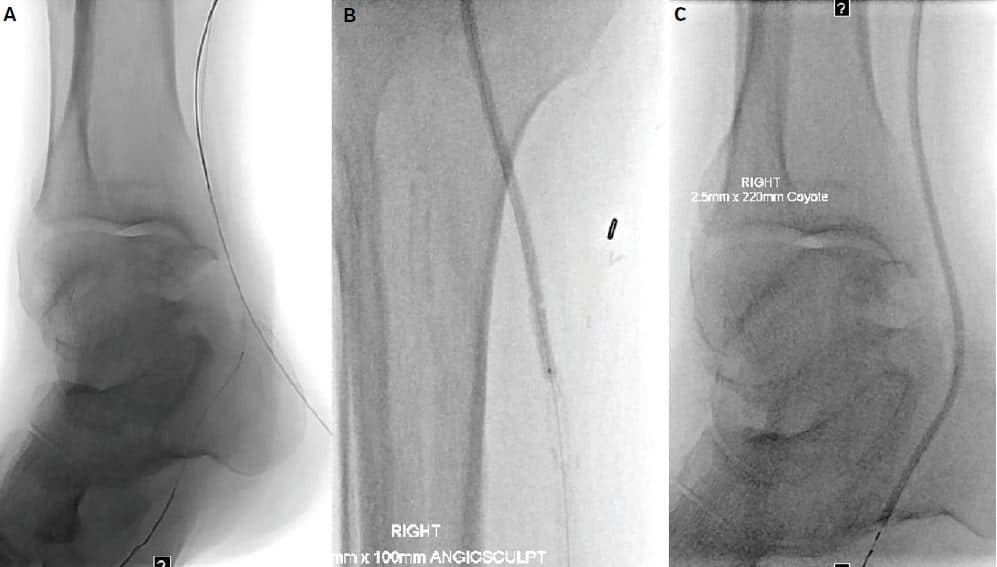

Figure 4. (A) Reversal of the retrograde flossed wire into the distal lateral plantar artery to have a single antegrade wire. (B & C) Serial angioplasty of the entire posterior tibial artery.

The patient has been evaluated several times by vascular specialists (surgical and interventional), with the consensus that even after performing angiograms, there were no endovascular or surgical revascularization options, and a major amputation was recommended and planned. The patient was sent to my clinic by his podiatrist, who had known from our prior discussions that advanced peripheral vascular disease and CLI cases do deserve multiple opinions.

The patient and family reported that he was experiencing constant rest pain at the plantar side of the foot and towards the wound, without fever or other symptomatology. His diabetes was being well managed, now with an A1c of 6.2 and glucose levels consistently in the normal range. The TMA wound showed eschar with non-healing areas despite optimal wound care. He had palpable femoral and popliteal arteries. No palpable dorsalis pedis (DP) or posterior tibial (PT) pulses were present, however, barely audible tones were noted. Noninvasive testing showed monophasic waveforms of the PT and DP, and we were unable to discern an ankle brachial index. After discussion with the patient and family, the decision was made to attempt revascularization.

Over the years, increasingly innovative endovascular salvage approaches and techniques have been developed, which in many cases have prevented major amputation for patients at the “terminal arterial cancer” stages.

Technique

Figure 5. (A) Reversal of the retrograde fl ossed wire into the distal lateral plantar

artery to have a single antegrade wire. (B & C) Serial angioplasty of the entire

posterior tibial artery.

The patient was brought to the interventional radiology (IR) suite and placed under general anesthesia due to his baseline pain intolerance and inability to remain still. Ultrasound guided access was obtained in the right common femoral artery in the antegrade direction (after review of prior outside hospital angiogram showing no inflow issues). Our initial angiogram showed a patent superficial femoral artery, profunda, and popliteal arteries. The proximal hood of a popliteal origin to distal posterior tibial artery (PT) bypass was noted with no flow. The anterior tibial artery (AT) and peroneal artery were chronically occluded after their origins. The majority of the lower leg was being supplied by a collateralized network, with subtle reconstitution of the most distal aspect of the PT and occlusion of the plantar arteries beyond their origin. A very faint short 2–3 cm segment of the DP artery was noted on delayed imaging.

A braided sheath was advanced into the distal superficial femoral artery. After a failed brief attempt at antegrade PT recanalization, retrograde pedal access was obtained by accessing the distal PT just above the calcaneus under ultrasound guidance. Using a 0.014˝ guidewire and support catheter, I successfully recanalized the occluded bypass graft and obtained flossing access through the right groin sheath. Sequential balloon angioplasty was performed with long tapered 0.014˝ balloons as well as scoring balloons. The retrograde wire was reversed, and the lateral plantar artery was successfully recanalized, followed by serial balloon angioplasty. I don’t typically use retrograde sheaths in my practice, so I obtained pedal access hemostasis during this angioplasty. The completion angiogram showed widely patent flow through the popliteal to PT bypass and through the plantar arteries.

Figure 6. (A) Retrograde access into the small dorsalis pedis artery. (B) Failed subintimal course of antegrade and retrograde recanalization attempts (red arrow). (C) Successful luminal re-entry of the retrograde wire into the popliteal artery after balloon-assisted subintimal disruption (not shown).

In order to maximize direct perfusion, a decision was made to revascularize the AT as well. Retrograde access with ultrasound guidance into the DP was obtained. A 0.018˝ guidewire and support catheter were advanced through the occluded AT. This resulted in a mostly subintimal course in the mid and proximal segments. Advanced techniques to regain luminal entry were attempted, including antegrade balloon assisted subintimal disruption (CART), which ultimately allowed retrograde passage into the popliteal artery true lumen. This was snared and flossed out of the right groin sheath.

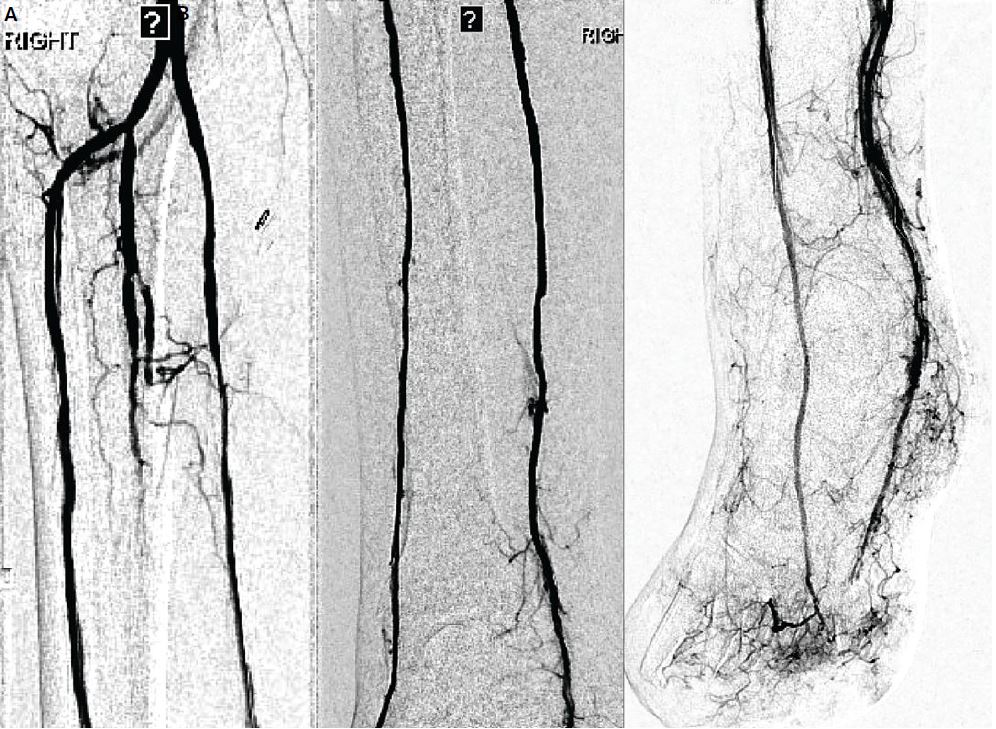

In order to protect the luminal integrity of both origins, simultaneous kissing balloon angioplasty was performed of the AT and PT. During intermittent angiograms, it was noted the bypassed PT would not stay patent, despite adequate heparinization, angioplasty, and evaluation by intravascular ultrasound. There did, however, appear to be an area of irregularity and recalcitrant stenosis at the distal bypass anastomotic region. Therefore, a 3 mm coronary drug-eluting stent was deployed across this area. The completion angiogram demonstrated patent two-vessel runoff with direct TMA wound hyperemia. A repeat angiogram was performed after 15 minutes to ensure on-the-table patency.

Figure 7. (A–C) Completion angiogram after serial angioplasty shows intact two vessel runoff by the anterior and posterior tibial arteries with intact plantar and dorsalis pedis as well as direct wound angiographic blush.

The patient was discharged home 3 hours later with follow-up scheduled in the IR clinic as well as with his podiatrist. After 3 weeks, during IR followup, the patient reported resolution of rest pain, and consensus with the podiatrist confirmed evidence of healing with granulation formation. A noninvasive study showed triphasic PT and biphasic DP waveforms. Our patient will be continually monitored during the months ahead, and close consultation with the podiatrist will be continued.

In this case, we describe a patient facing major amputation after prior surgical bypass and progressive transmetatarsal amputation (TMA) site wounds, with successful endovascular revascularization.

Discussion

CLI intervention for limb salvage requires many advanced and innovative techniques. Anecdotal experience has shown that failed chronically occluded bypasses can at times be revascularized, and this should be attempted if there are limited options left. This case demonstrates one such example. Also, for limb salvage, as many vessels as possible need to be revascularized to provide the best chances for wound healing. However, repeat interventions may be required at times to counteract the unacceptably high mortality rate that is too common in these patients.

The general awareness of the progressive and devastating nature of CLI is slowly but luckily growing, thanks to the efforts of many operators, societies (including CLI Global), and patient testimonials. However, we are far from achieving an acceptable level of uniform high-level care delivered to patients with limb-threatening wounds and disease. Until that time, it is imperative that CLI be treated as “terminal arterial cancer” and patients be referred for, and approved for, second and third opinions to high-level centers and operators, similar to multidisciplinary cancer centers. We need centers of excellence in CLI so that all patients have access to the best chances of survival.

Dr. Madassery is an Assistant Professor, Vascular & Interventional Radiology, at Rush University Medical Center & Rush Oak Park Hospital, Illinois, and CLI Program Director.

Dr. Madassery is an Assistant Professor, Vascular & Interventional Radiology, at Rush University Medical Center & Rush Oak Park Hospital, Illinois, and CLI Program Director.

Follow Dr. Madassery on Twitter: Follow @KMadass

Disclosure: Speakers bureau for: Cook, Abbott, Penumbra. Consultant for Cardiva. Advisory board for: Philips, Boston Scientific.